dstpierre/tpl a library making html/template more tolerable

Software systems builder

Do you also find the html/template package to be a tad rough around the edges. I created an opiniated helper library that helps me with structuring, parsing, and rendering of HTML templates in Go.

Each time I start a new Go web application that requires templating, I pass through the following phases.

- How did I do that last time to have layout pages already?

- Why does the

html/templatepackage not parse my templates as I want them parsed? - How do we have pieces of templates reused across other pages?

When you think about it, it's normal to forget how to structure and parse the templates since we don't have to do it often—mostly just when starting a new project.

Still, I got tired of it and decided to create an opinionated library that would handle most of what I wanted regarding templating to remove this part from my mind.

I've been talking about this on the pod. In the last year, I took a small detour into Python/Django, completing 3-4 projects with that stack. I have to admit that the way templating is handled is easier, like, way easier. I wanted to see if we can have the same simplicity with the html/template package.

I'm well aware of the templ library. I prefer sticking with the stdlib and raw HTML files.

The library is: dstpierre/tpl

What do I mean by "it's an opinionated library"?

Structuring is a fundamental aspect that consistently surfaces in the journey of most Go programmers when creating packages. Structuring templates, to me at least, isn't different.

I want rigid and defined directories and file structures for my templates.

Here's what I settled for:

templates

├── _partials

│ └── nav.html

├── app.html

├── layout.html

├── translations

│ ├── en.json

│ └── fr.json

└── views

├── app

│ ├── dashboard.html

│ └── account.html

└── layout

└── user-login.html

Layout templates

The layout templates are at the root of the templates directory.

A layout is a parent HTML file that wraps different views of your application. It can be as simple as having one for signed-in users and one for public users, or it could be as complex as having ten layout templates for multiple scenarios.

In the tree above there's two layouts:

templates/layout.htmlfor non-authenticated users.templates/app.htmlfor authenticated users.

The layout must include a block directive that gets filled by the view.

templates/layout.html:

<html>

...

<body>

<h1>Content from the parant</h1>

{{block "content"}}{{end}}

<p>The above came from the view</p>

</body>

</html>

Views

Views are wrapped in layout and usually match the current route / URL the user is viewing. You typically have multiple views for the same layout.

You place your views in the template/views/{layout}/{name}.html.

Each layout files have a sub-directory with the same name without the .html extension in the templates/views directory.

In the tree example above we have the following view templates:

templates/views/app/dashboard.htmlthat usesapp.htmlas parent layout.templates/views/layout/user-login.htmlthat uses thelayout.htmlas parent layout.

templates/views/layout/home.html:

{{define "content"}}

<p>This is the content from the view template.</p>

{{end}}

Reusable components

The _partials sub-directory allows you to save small HTML components that can be rendered in layouts and view templates.

Those components are always parsed with all layouts and views so they can be used in both.

Let's take the _partials/nav.html as an example:

templates/_partials/nav.html:

{{define "nav"}}

<nav>Your navigation HTML here</nav>

{{end}}

Inside the app.html layout:

templates/app.html:

<body>

{{template "nav" .}}

</body>

Notice how the partials has their own defined name and we use that with the template directive {{template "custom-name-from-partial" .}} to render the component.

Translation

In Canada we have two official languages, English and French.

I'm used to having most of my projects needing translations and internationalization.

The templates/translations directory allow for translation values to be available in the layouts, views, and components.

The library also exports functions that can be called from your Go code as well.

The files in the translations directory are JSON files with the following schema:

templates/translations/en.json

[{

"key": "the-key-you-use",

"value": "The value displayed"

}]

You use translation like this:

<h1>{{t .Lang "the-key-you-use"}}</h1>

There's ways to use translation values with dynamic parameters akin to the fmt.SPrintf for example. You can read the documentation for all the details.

Rendering templates

There's two things you'll need to do before you can start rendering templates.

1. Initializing

The library wants to parse your template structure and prepare everything so your application can start rendering templates.

Here's an example:

package main

import (

"embed"

"net/http"

"github.com/dstpierre/tpl"

)

//go:embed templates/*

var fs embed.FS

func main() {

// assuming your templates are in templates/ and have proper structure

templ, err := tpl.Parse(fs, nil)

// ...

http.HandleFunc("/", func(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request)) {

data := "this is your app's data you normally pass to Execute"

// This hs what tpl expects

pdata := tpl.PageData{Data: data}

if err := templ.Render(w, "app/dashboard.html", pdata); err != nil {}

}

}

You first need to call the tpl.Parse function. It will return a tpl.Template you keep in your application. This type allows you to render templates.

I like to have a global variable like this:

var templ *tpl.Template

func main() {

var err error

templ, err = tpl.Parse(fs, nil)

}

2. Call the Render function

The tpl.Template exposes a Render function that expects the following parameters:

- The

http.ResponseWriter. - The name of the view with its parent layout (i.e:

app/dashboard.html). - The

tpl.PageDatastructure where you can fill your data and more.

This is the tpl.PageData structure:

type PageData struct {

Lang string

Locale string

Timezone string

XSRFToken string

Title string

CurrentUser any

Data any

}

When using the stdlib html/template package you pass one structure to your template and access it via the {{.}} in your templates.

Using tpl you're always receiving a tpl.PageData in your templates.

Your data is in the Data field. For instance, here's an example template:

templates/views/app/dashboard.html:

{{define "content"}}

<h1>Hello {{.CurrentUser.Name}}</h1>

<p>Your XYZ list</p>

<ul>

{{range .Data}}

<li>{{.ID}} - {{.Something}}</li>

{{end}}

</ul>

{{end}}

In the above example we would have pass an array of some types to the Data field of the tpl.PageData and filled the CurrentUser with a User struct.

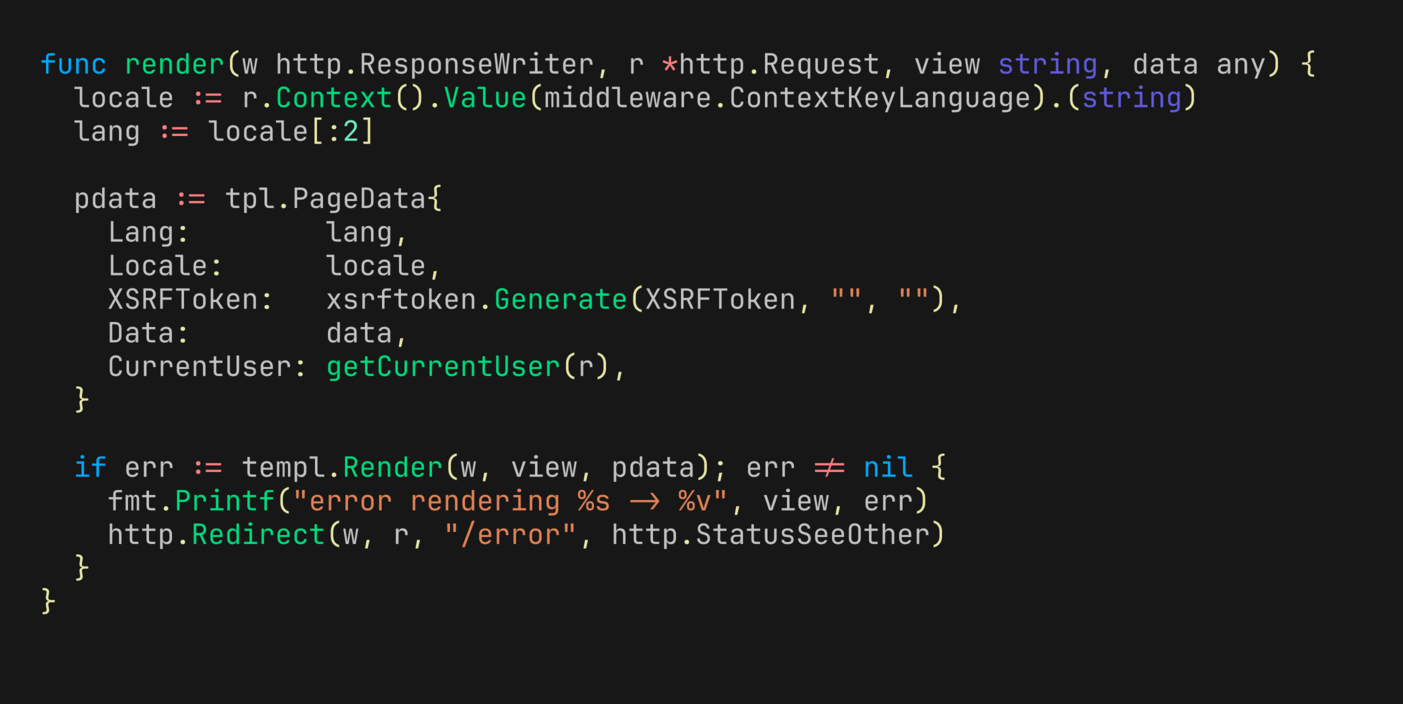

I tend to have one helper function in my application to help with rendering and filling the tpl.PageData structure.

func render(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request, name string, data any) error {

d := tpl.PageData{Data: data}

// example getting current user or nil from request

d.CurrentUser = getCurrentUser(r)

// example getting locale from request's context that came from middleware

d.Locale = r.Context().Value(ContextKeyLocale).(string)

// generate an XSRFToken

d.XSRFToken = xsrf.Generate(XSRFTokenKey)

return templ.Render(w, name, d)

}

In my HTTP handlers I call that function when ready to render something:

func (Dashboard) home(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

user := getCurrentUser(r)

list, err := db.Q.GetDashboardList(context.Background(), user.ID)

//...

render(w, r, "app/dashboard.html", list)

}

From the point of view of my handlers using tpl of the raw html/template is mostly the same due to the above helper function.

It's a bit more tolerable

I've been using this library in two project so far and I enjoy it more than using the straight up html/template.

Mainly because it forces me to organized myself, find a standard way to structure and parse my templates and get some orders in all that chaos.

An additional bonus I wasn't expecting is that it works great with HTMX.

I created a templates/raw.html layout that does not do anything other than having the block for the view to inject itself:

templates/raw.html:

{{block "content"}}{{end}}

Some of my HTTP handlers and directly return just what the view need when an HTMX partial page update is requested, for instance:

templates/views/app/dashboard.html:

<form hx-post="/path/to/add/handler" hx-target="#list">

<input type="hidden" name="xsrf-token" value={{.XSRFToken}}>

<input type="text" name="value">

</form>

<ul id="list">

{{template "dash-list" .}}

</ul>

The handler:

func (Dashboard) add(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

user := getCurrentUser(r)

r.ParseForm()

validateToken(w, r)

newValue := r.Form.Get("value")

db.Q.AddDashboardValue(context.Background(), user.ID, newValue)

list, err := db.Q.GetDashboardValues(context.Background(), user.ID)

render(w, r, "raw/dash-list.html", list)

}

And finally the raw template:

templates/views/raw/dash-list.html:

{{define "content"}}

{{range .Data}}

<li>{{.Value}}</li>

{{end}}

{{end}}

Well, it's not Django's template, but it's 10x, heck maybe 20x more comfortable than what I was doing before.

Feel free to check it out and hopefully you find it useful for your as well.